To find the position and the related measurements of all numbered blocks,

see the

CHEOPS SHAFTS

drawing

at the CYBER DRAWINGS

page.

All

copyrights Rudolf Gantenbrink 1999

The lower end of the shaft begins with a 2.63 meter horizontal section through the first block, which, like all the wall stones of the King's Chamber, is made of granite. At this point the shaft is made up of three stones.

At Block No. 2 the shaft angles upward and simultaneously bends to the West. The connection of this block to those below is unusual (for details, see

CHEOPS SHAFTS drawing at the

CYBER DRAWINGS page).

From Block No. 2 up to the beginning of Block No. 5, the block floors have been almost completely destroyed. In 1817 Capt. Caviglia dug open this section from below to form a tunnel which follows the bends and angle changes of the shaft. Thanks to this tunnel we were able to conduct very exact measurements of this section of the shaft

(see

CAVIGLIA TUNNEL drawing at the

CYBER DRAWINGS page).

Two interesting conclusions can be drawn from the shaft bends and changes in angle of ascent:

1. Until 1993, when we discovered that the lower northern shaft also bends to avoid the Great Gallery, it was generally assumed that the bends in the upper northern shaft were simply the result of a planning mistake made by the pyramid builders. In other words, not until actual construction was underway did the builders supposedly realize that extension of the upper northern shaft conflicted with the Great Gallery. Based on our present knowledge, this assumption no longer makes sense.

The northern shafts' structural conflict with the Great Gallery was obvious to the builders much farther below, during construction of the shafts emanating from the Queen's Chamber. Based on the experience gained there, the builders could have shifted the King's Chamber shaft inlets farther to the West, in order to correct their "planning mistake" without great effort. Instead, the builders repeated the conflict situation, a fact which again cost them immense time and energy.

There is only one reasonable answer to this apparent dilemma: the position of the shaft inlets in the chambers was critically linked to an exact spot, so no shifting of the inlets could be tolerated. (For the actual positioning of the inlets see

CYBER DRAWINGS at THE FINDINGS page)

2. The master builders of ancient Egypt were totally out of their element when it came to constructing this shaft sequence. In a 1997 lecture I outlined the limited conditions under which they were capable of applying the principle of angle bisection. For instance, they did so with great precision in the roof constructions of the King's and Queen's chambers, as well as at the original pyramid entrance. (See the

PUBLICATIONS page.)

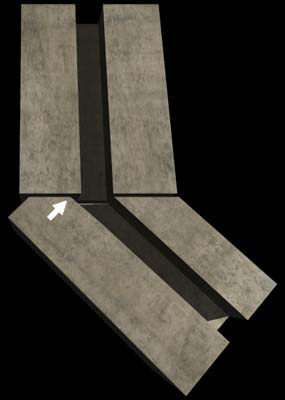

But apparently they didn't have even a vague notion of how to apply this principle to building the shafts. The end of one block was cut at a right angle, to which the end of the next block was simply adapted. For this reason the shaft width fluctuates considerably, in some cases reaching only two-thirds of the average value.

(See

CAVIGLIA TUNNEL drawing at the

CYBER DRAWINGS page.)

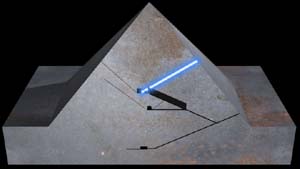

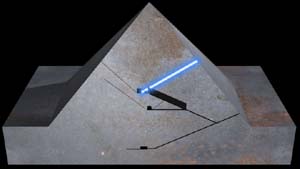

Move your cursor over the image to see the problem

the builders faced. Either the connection was not

perfect or the shaft width diminished at each bend.

(Shaft shown upside down.)

ALTERNATIVE VIEW

After the

CAVIGLIA TUNNEL, from Block No. 6 on, the shaft continues in the usual form. The angle between this point and the point of the shaft's outlet on the flank of the pyramid (we measured both points) is 32.60°.

From this point on, the shaft seems to ascend at a constant angle. But we did discover a slight bend in the longitudinal axis (see

BENDS 3D at the

CYBER DRAWINGS page). By comparing the relative positions of Upuaut-1's tow line, which ran parallel to the shaft, we were able to determine that this bend begins at the end of Block No. 20.

Block No. 23, measuring 4.37 meters, is the longest we found during our investigation. Its ceiling is partially unfinished.

The ceiling of Block No. 24 is also unfinished.

From the end of Block No. 25 to Block No. 32, where it emerges on the pyramid exterior, the shaft runs through a tunnel dug by unknown plunderers.

The digging of this tunnel, which we came to refer to as the "Mankiller", completely destroyed the ceiling and east wall of the shaft. The west wall, still intact along the entire length of the tunnel, displays no special features. Thus, an arrangement of niches of the kind we discovered in the upper southern shaft (see

UPPER SOUTHERN SHAFT , BLOCK No. 23) cannot have existed here, otherwise we would have found at least some trace of a recess in the undamaged west wall.

The "Mankiller" tunnel is accessible from the outside of the Pyramid, so we could manually measure the angle of shaft inclination through this section. The average angle is 31.20°, determined by 5 measurements made over a length of 11 m.

THE UPPER SOUTHERN SHAFT

THE LOWER NORTHERN SHAFT

THE LOWER SOUTHERN SHAFT

|